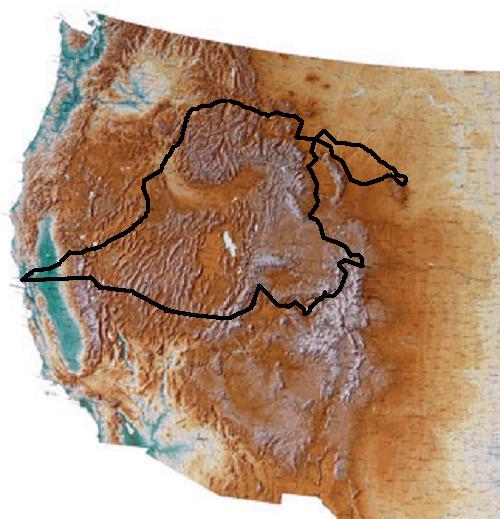

Hofey's Ride

Follow Hofey's progress, pinpointed daily on Google Maps

July 30 290 miles

Packed up, strapped down, and chomping at the bit by 8:00am. For Hofey, the adventure begins in San Rafael, California. He joins his riding buddies - George, Dan, Dave and Chris - and the first day is spent getting out of town and into the wilderness and adjusting to the road. Leg cramping and camping top off the day at peaceful Twin Lakes in the Eastern Sierra, near Mono Lake. Day's end: Bridgeport, California.

July 31 370-400 miles

After riding the cool hours of the morning, it's breakfast time in Lee Vining, California, then on into the desert with NO GAS FOR 190 MILES to Tonopah, Nevada. Top temp for the day about 95 degrees. Riding is bearable in a thoroughly water-soaked shirt. Is it a mirage? No, it's Rachel, Nevada, Area 51 and UFO country, where a sun-baked biker can cool his flying object at the Little A'Le'Inn. (Get it?) Day's end: Caliente, Nevada.

August 1 360 miles

The first stop of the day is for coffee at 8:00am (after riding 75 miles already) at Cedar City, Utah. Then off again to behold the flaming red canyons of Cedar Breaks and Capitol Reef (← catch those videos) two of Utah's magnificent national parks. Weather, perfect. But after a long day, rather than pitch tents, the boys slack overnight in a motel and are dead to the world by 9:30. Day's end: Price, Utah.

August 2 419 miles

They're up 'n' at 'em early again, for another spectacular day of riding, first through Green River, Utah then the ever amazing Moab, Utah. Eventually the road takes them across the state line and into Grand Junction, Colorado, then Gateway, Colorado, and Ridgway, Colorado, for some of the most exciting trails of the wild west. The weather is pretty exciting too - no less than three thunderstorms. But that's why real bikers do this sort of thing. Day's end: Montrose, Colorado.

August 3 324 miles

Today's journey leads further north into the higher elevations and thinner air of the Rocky Mountains. First wet-yer-whistlestop is Crawford, Colorado. By 9:30 it's Hotchkiss, Colorado, 10:30: Paonia, Colorado, 11:30: Carbondale, Colorado. When you hit celcius and have to pull on your chaps and earflaps in August, you know you're in the Rockies. By 2:30 they've reached the well-heeled boot town of Aspen, Colorado (where Hofey has a Kevin Costner sighting), then it's over the Continental Divide through Independence Pass at 12,095 feet, then down to Leadville, Colorado at a mere 10,152 feet. The entire day is packed with amazing sights. Did I mention how envious I am? Well, perhaps I'm not. After getting separated from the group, Hofey spots a mean thunderbumper looming ahead and pulls over to put on his rain gear and hide in a gas station. He waits. It pours. Then off in the distance come the others, completely drenched. He just smiles. They all decide to turn in early and he and George head for a motel in town. The others camp in the rain. He phones me at 8:00pm to say he's looking at a rainbow when suddenly it's pierced by lightening. He's ready for bed and it's not even sundown. Night night, Hofey. Sleep tight and don't let George bite. Day's end: Kremmling, Colorado.

August 4 262 miles

Following a late breakfast (after what must have been a rough night for the campers) our merry band of bikers set forth at 8:30. About an hour later, outside of Steamboat Springs, Colorado, the inevitable Iron Monk event takes place - somebody's bike breaks down. So, while Chris makes repairs, Hofey repairs to the golf course. (Well it just goes to show you, it's always something, if it's not a bike widow it's a golf widow.) By 11:00, Chris's bike makes a miraculous recovery and off they go to Walden, Colorado. Then they snake their way around the Poudre River Canyon and turn north across another state line with the Medicine Bow Mountains to the west and the Laramie Mountains to the east. Unfortunately, the trials and tribulations of the day are not over. About 3:00, along comes a Category 5 with blinding rain, hail, snow and 50 mph winds. So they just hole up in a gas station for an hour and wait. Once the storm blows over, the ride is magnificent. Finally by 5:00, with the day's destination reached, no time is wasted finding a fleabag motel and a close by saloon. Hofey, however, has another idea. Sushi. Right next door. Best in the world. Where else but in the Great North West? Day's end: Laramie, Wyoming.

August 5 456 miles

According to Chris, Hofey tossed and turned and talked in his sleep all night, at one point shouting "Take your medication!" Hmm musta been something he ate. One cowpoke octopus sashimi too many, I reckon. Nevertheless, the day begins early over Route 130 and by 7:30am the Monks are in Centennial, Wyoming for breakfast. No particular route is planned but they head toward the Upper Platte River Valley across the Snowy Range Scenic Byway and, true to Iron Monk form, in the exact opposite direction of Sturgis. For not knowing where they're going, they certainly go. This is cattle country, flat and dusty. Not much to see here, folks, git along. Unhindered by rain all day, they travel a couple hundred miles to Lander, Wyoming. From here they follow the Bighorn River into injun territory, or rather, the Wind River Indian Reservation, to Riverton, Wyoming. Continuing northeast, they cross the Boysen Reservoir to Shoshoni, Wyoming, then straight up the valley between the Absaroka Range and the Bighorn Mountains. Bighorns? Yup, they're everywhere - deer, elk, buffalo, and cattle by the thousands. The mighty Iron Cowpokes try to make it to Red Lodge but by 6:00pm they're ready to pitch camp. That's okay. They rode all the way up the state of Wyoming. And they can see Beartooth where seldom is heard a discouraging word and the skies are not cloudy all day. Not a drop. Day's end: Cody, Wyoming.

August 6 112 miles

Today Hofey veers off on his own. The rest of the Iron Monks visit the Buffalo Bill Museum in Cody, then split for Red Lodge, Montana. Hofey goes further north through Yellowstone Country to see his buddy Ed, who takes him flying over the area, yes flying, in his Cessna 150. And the word today: No Sturgis. Well maybe. Stay tuned... Abort! By afternoon Sturgis is back on. Hofey and Ed and two of Ed's buddies, all bikers, are planning to meet the Iron Monks in Sturgis. After slurping 3 beers for 3 dollars at a garage-turned-brewery, then supervising the installation of a new lawn (heh), the day finishes with Ed's lip smacking mouthwatering barbecued ribs on the grill, corn-on-the-cob and homemade potato salad. What hospitality! Not to mention a place to sleep. Hofey heaven. Day's end: Billings, Montana.

August 7 308 miles

In expectation of a hot dusty ride, Hofey, Ed, Jerry and Jim (heretofor known as The Flying Pistons) leave Billings shortly after 7:00am. Hofey had a great night's sleep and he's ready to roll eastward for the rally. He's been seeing bikers everywhere for days, but now the place is crawling with them. By 9:00am they've passed through Little Bighorn Battlefield by way of Custer's Last Loop and the Pistons fly into Sturgis midafternoon. For 10 bucks they grab a spot to pitch their tents, 8 miles north of Sturgis, at the Broken Spoke Campground. Massive swimming pool, 10-12 food vendors. Hofey has no complaints except for one - the women without clothes who should have clothes. Avert your eyes, Hofey, avert your eyes! Day's end: Sturgis, South Dakota.

August 8 116 miles

This is it. Hog heaven. Sturgis was the first of the biker rallies and, after 70 years, it's still going strong. In testament to that, two days before the event the place is already packed. Because of the anniversary, they're expecting an estimated 800,000. The actual crowd count won't be determined until after the event, when the sewage is measured. No shit, er, really. From what I saw at the 60th, this is what it's about: a motorcycle mecca, a carnival, a freak show, a city-wide saloon, a vendor's paradise, a strip mall and a strip joint. In one word: Testosterone. If it gets to you, get out of town. There's some great road out there.

Early morning and it's already hot and humid. Hofey takes his bike out for a spin to Rapid City, South Dakota and returns to camp drenched in sweat. Between siestas, the pool is the place to be. The Monks are now here, so Hofey cruises back into town with his eyes peeled. He spots George, Dan and Chris and they hang out looking at trailers. Right about now one with some air-conditioning must be look pretty good. Like the one you have waiting for you back home, Hofey. You know, the one with the special attachment? Day's end: Sturgis, South Dakota.

August 9 157 miles

Hofey calls at 8:00am, tells me to look up:"MSEPevents.com" and enter event code 10112, frame 190. Someone just caught him in the act of riding. What a racket. You can't even look at it without registering your email address and then they want you to buy it. The Flying Pistons are off to see the bike shows but Hofey breaks off solo again. He'd rather see Mount Rushmore and Crazy Horse. (Are you out there T?) If you stand still it's blistering but if you ride you catch a breeze. That translates to gorgeous. So he rides to Deadwood, South Dakota too. Swings back around 4:00. I get another call from him and he's sitting in his tent with 40 mph winds. Suddenly we lose connection and I figure he blew away. This is repeated several times before we can actually speak to each other. He wants me to call him tomorrow morning at 6:00 to wake him up. Looks like they've seen enough that they can come home. Of course that means another 4-5 days riding. Better get a good night's sleep. Yes, I'll wake you up. Day's end: Sturgis, South Dakota.

August 10 486 miles

When I talk to Hofey at 6:00 the others are still asleep. Three hours later he calls from the road to say he's lost them and they're not returning his calls. By 9:45 he's heading west by himself on Route 212 toward Yellowstone. In my inimitably helpful manner, I warn him about two escaped killers who've made their way into the area from Arizona. (You can't make this stuff up.) He'll be shooting for Sheridan, Wyoming. At 2:30 he stops in Billings and, within minutes of taking off, Chris calls. So Hofey has been found and all the Iron Monks are traveling together over 90 West to Holter Lake, Montana. Well ain't that great; Holter Lake, where a deadly shoot-out took place in 1987 with two other dangerous fugitives. Can't make it up. At 6:00pm a call comes in from the Corral Motel and, yes I will accept charges. Didn't make it to Holter Lake *whew* but they have nevertheless put a respectable 486 miles onto their mileage. Day's end: Harlowton, Montana

August 11 478 miles

Well, this morning the Monks are behaving themselves, playing very nicely together, no one left behind, yet. They ride across Route 12 the entire day, through half of Montana, one big ass state. Route 12 follows the course of the Lewis & Clark Expedition of 1804-1806, where signs detail the route at several points. The surrounding forests and mountains make for spectacular scenery. The Monks depart Harlowton at 8:00 and by 9:00 they have passed through White Sulphur Springs, Montana, stopping in Townsend, Montana, "the first city on the Missouri River" located at the southern tip of Canyon Ferry Lake. There they jog north following the western curve of the Helena National Forest. This leads them to the state capital, Helena, Montana. With Chris way ahead, and Hofey way behind, they both somehow make it to Missoula, Montana by 1:30. But George, Dan and Dave go missing, probably visiting a Harley dealer along the way. (I wonder if Lewis & Clark stopped at the Harley dealer?) From here they must decide whether to try for Lolo Pass, but a 60% chance of heavy rain might decide for them. BREAKING: It's official, as of 3:00 this afternoon, Hofey is no longer traveling with the Iron Monks. They stopped to rest in a beautiful area just outside of Missoula, at the amazing Lumberjack Saloon, where they were having such a great time they just didn't feel like leaving. Well, for those of you who know Hofey, he can't drink and he can't sit still. So he bought them all a beer, gave them all a hug, bid them all a safe journey, then struck off all by himself. Right over Lolo Pass and into eight (8) rainstorms. Musta been some kinda Native American cleansing ceremony. I don't know. Then down, down, deep into the bowels of the canyon at the confluence of the Salmon rivers he went, into a tiny town where US 95 becomes the main street. Watered his horse by 7:00; by 8:00, hit the hay. Day's end: Riggins, Idaho.

August 12 562 miles

Out the door at 6:56am. Traveling alone has its advantages. Wending his way south through the canyon, the air is foggy and cold, and when he pulls into Payette, Idaho at 9:00, the chaps do not get pulled off. He has Crispy Creme Doughnuts for breakfast. Always good for the road. No news on the other Iron Monks. Probably won't for the rest of the trip unless someone out there adds it to the comments. However, I do have an update on Bonnie & Clyde: they're still at large. By late afternoon, Hofey has hauled-ass to Lovelock, Nevada where he says he will stay the night. At 5:15 he calls from a hotel room in Reno - down the road a piece another 100 miles - where he finally lands for the day. After a bite to eat, he plays the slot machines a bit in the casino, and sinks into bed early. What a very long distance he has ridden. 562 miles. All so that he can be home by tomorrow. Day's end: Reno, Nevada

August 13

Friday the 13th - what a lucky day! Hofey's coming home! At 6:45 he sets out from Reno on the final leg of his journey, with only a few more hundred miles to go. It will be good to have him back. George, Dan, Dave and Chris are still out there, so if you have any news on them, please update us in the comment section below. I've changed the settings to make it as simple as possible. Godspeed, Iron Monks. We love you. After 15 days and 4,933 miles on the road, Hofey reached his final destination, home, at 11:00am on Friday the 13th of August 2010. Day's end: San Rafael, California.

Since July 30th I've had a lot of fun bringing you the daily adventures of Hofey's two week motorcycle trip. I hope it has given you a small sense of excitement of their enormous undertaking. Thanks to everyone for following along. For the loved ones of the Iron Monks, I hope it has helped to bring you a little bit closer to them. Ride free!

Follow Hofey's progress, pinpointed daily on Google Maps

Please join the conversation and let us know who you are.

1. Scroll all the way down to "Post a Comment"

2. Type your message within the box

3. In the "Comment as" drop-down menu, select "Name/URL"

4. Type in your name, ignore URL, click "Continue"

4. Click "Post Comment"