We hold these truths to be self-evident:

that all men and women are created equal.

The Other Independence Day

by Robyn Blumner

The Salt Lake Tribune | July 5, 2010

Women have an Independence Day, too. Seneca Falls, N.Y., was the place of our declaration’s signing, a community of reformers and abolitionists in pastoral western New York, not far from the homes of William Seward and Harriet Tubman. Here, the organizers of the First Women’s Rights Convention on July 19-20, 1848, imagined a just future for their daughters, just as decades earlier, in steamy Philadelphia, Jefferson, Franklin and Adams envisioned one for their sons.

The document they produced, the Declaration of Sentiments, bears the signatures of then 32-year-old Elizabeth Cady Stanton (who refused to vow “to obey” in her marriage ceremony) and Lucretia Mott, along with dozens of other women and men. To most of us, the prose of their declaration will ring a (liberty) bell. It begins, “When, in the course of human events ... “ and states “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal.” (Emphasis added.)

Whether it’s 1776 or 1848, ideas don’t get much more radical than that.

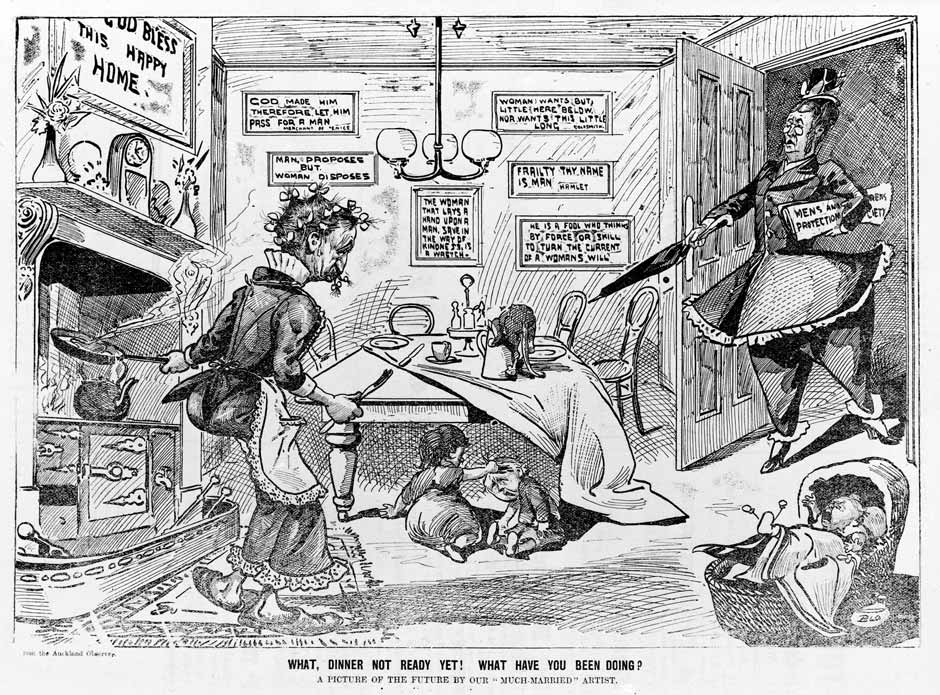

The declaration’s list of abuses and usurpations were not that of the long-dead King George but of male society that usurped the rights of women and subjugated women within marriage. Women could not vote; married women could not own property; they were denied higher education, and their husbands had legal dominion over them.

The law viewed women as little better than children, much like the way a king sees his subjects. These ladies’ parallel to the rebellion of the founders was more than apt.

As a kid with a healthy sense of right and wrong, I remember being both outraged and befuddled over the battle American women waged for suffrage. Women won the right to vote only 41 years before I was born. By Aug. 26, 1920, the day the 19th Amendment became law, American cities were so jammed with cars and trucks that the traffic light had been invented. Albert Einstein had already posited his general theory of relativity, and modern warfare included the use of airplanes.

Even as illiterate and criminal men enjoyed the franchise, highly educated American women continued to be denied it, decade after decade.

As a girl, I wondered how that could be. But now that my jaundiced eyes have seen the jealous nature of power and privilege, and the stinginess of so many who possess it, I don’t wonder anymore. Here is just a taste of entrenched male entitlement that passed as benevolent paternalism, found in a 1915 editorial in The New York Times titled “The Woman Suffrage Crisis”:

“The grant of suffrage to women is repugnant to instincts that strike their roots deep in the order of nature. It runs counter to human reason, it flouts the teachings of experience and the admonitions of common sense. Although women have other capacities ... they have never possessed or developed the political faculty. Without the counsel and guidance of men, no woman ever ruled a State wisely and well. The defect is innate and one for which a cure is both impossible and not to be desired.”

The editorial goes on to worry about women losing their “many precious privileges” if they enter the “hurly-burly of life.”

At the time this was written, nearly one in four women over the age of 10 was employed. In factories, they earned 25 to 67 percent less than men. Four years before this editorial, 146 garment workers including over 100 women died in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in New York City, many of them unable to escape the flames because the exits were locked. Where were those precious privileges women would give up if they had a say in government?

We all know that Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence was an incomplete manifesto, leaving out many from its guarantees of “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” The women and men who congregated at Seneca Falls filled in the largest remaining gap, and in doing so, they laid the foundation for the remarkable advancements of all women to come.

Independence Day comes twice for Elena Kagan, Nancy Pelosi and all the work-a-day women of this country. Seneca Falls started a revolution, and we’re still living it.

Women's Suffrage